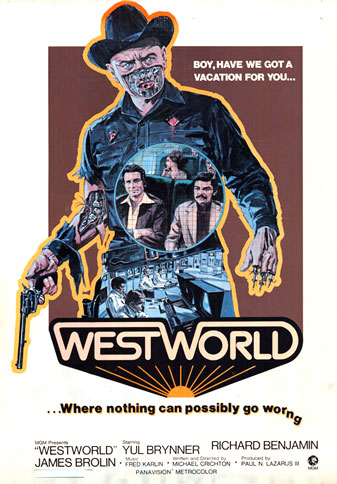

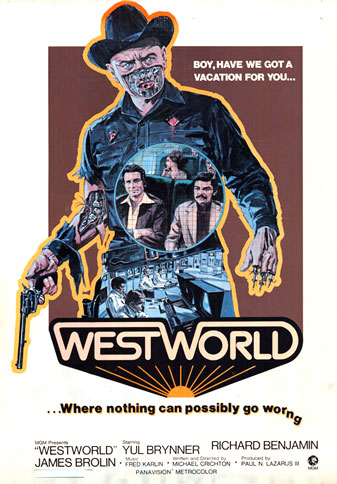

Westworld

In His Own Words

Everything’s digital these days, but it wasn’t always so.

In 1973, I made a movie called Westworld, which was a fantasy about robots. The film required us to show the point of view of the main robot, played by Yul Brynner. But what special-effects technique would best suggest a machine’s point of view?

I proposed a rather simple solution: to show the point of view of a machine, use a machine. I wanted to film the scenes and then manipulate the film with a computer.

Such a process had never been used for motion picture films before, and none of the special-effects houses even knew what we were talking about. At this time, film special effects were limited to purely photographic processes, such as solarization – the technique used, for example, to make the shimmery, bizarre-colored landscapes in 2001: A Space Odyssey. None of the special-effects houses had computers or were even thinking about them; all they could do were variations on photographic techniques. But photographic techniques look just like that – darkroom manipulation of the filmed image. I wanted a mechanical process.

Finally, we went to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. At least they knew what we were talking about. They explained that the technique had thus far been used for single images, because each required massive computer power. We were talking about two minutes of film, or 2,880 separate images. But they said they could do it: they could process two minutes of movie film. It would take nine months and cost $200,000.

Since the entire film had to be finished and released in six months at a total cost of $1 million, we had to look elsewhere. Eventually, John Whitney Jr., agreed to undertake the job in four months for $20,000. Working long hours and nights with giant mainframes, John was able to process only a few seconds of film a week.

But in the end, we got what we needed. Westworld was the first feature film to process imagery by computer. We obtained a sort of blocky, animated effect that was remarkable in 1973 – and a cliche seven years later, when similar imagery appeared in every thing from perfume ads to paintings by Salvador Dali.

Synopsis

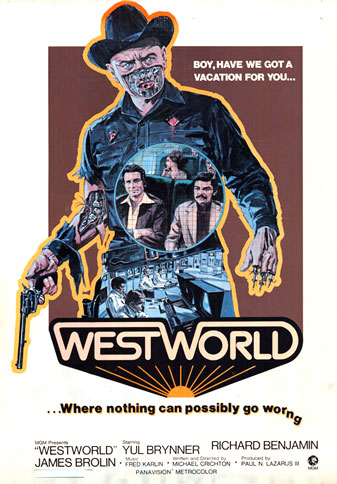

Two businessmen vacation in a recreated 1880’s frontier town, with realistic robot inhabitants. But when a programming error causes the androids to turn deadly, the two men are involved in a horrific battle for their lives against a gunslinger who is as lethal as he is unstoppable.

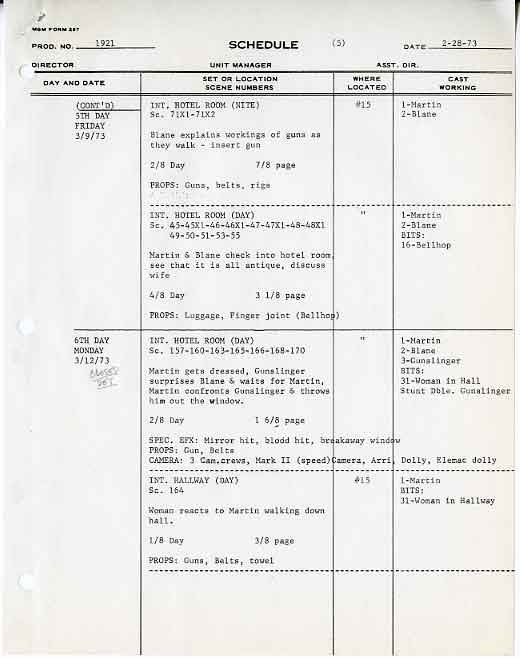

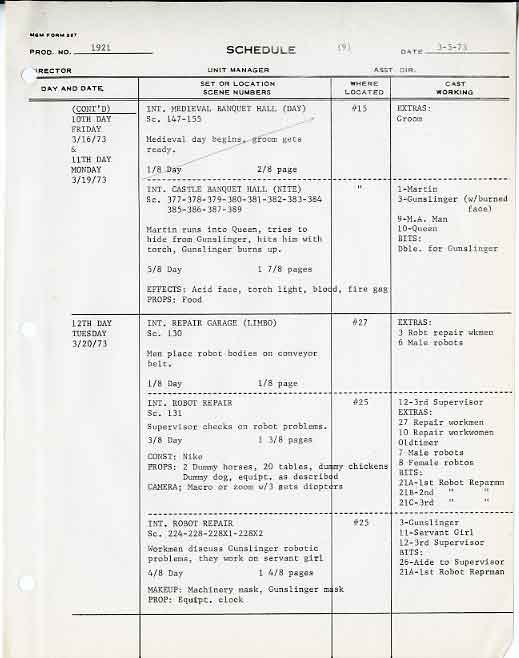

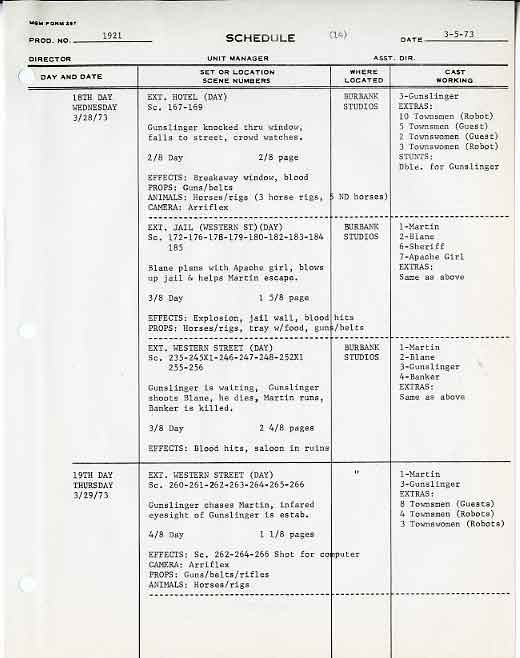

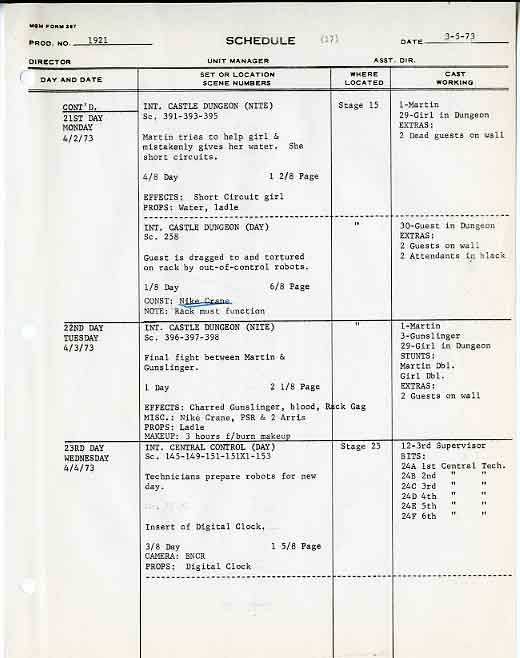

Michael Crichton directed Westworld from an original screenplay that he had written. MGM only agreed to let Michael Crichton direct his movie if he could make it for 1.3 million dollars (which was a very small budget even back in 1973) and if shooting lasted only 30 days. Michael Crichton reluctantly agreed and shooting began in the Spring of 1972. Here are a few of the shooting schedule pages.

In His Own Words

It [Westworld] didn’t work as a novel, and I think the reason for that is the rather special structure of this particular story. It’s about an amusement park built to represent three different sorts of worlds: a Western world, a Medieval world and a Roman world. The actual detailing of these three worlds—and also the kinds of fantasies that people experienced in them—were movie fantasies, and because they were movie fantasies, they got to be very strange-looking on the written page. They weren’t things that had literal antecedents, literary antecedents. They were things that had antecedents in John Ford and John Wayne and Errol Flynn—that sort of thing. In some ways, it’s a lot cleaner as a movie, because it’s a movie about people acting out movie fantasies. As a result, the film is intentionally structured around old movie cliche situations—the shoot-out in the saloon, the sword fight in the castle banquet hall—and we very much tried to play on an audience’s vague memory of having seen it before, and, in a way, wondering what it would be like to be an actor in an old movie.

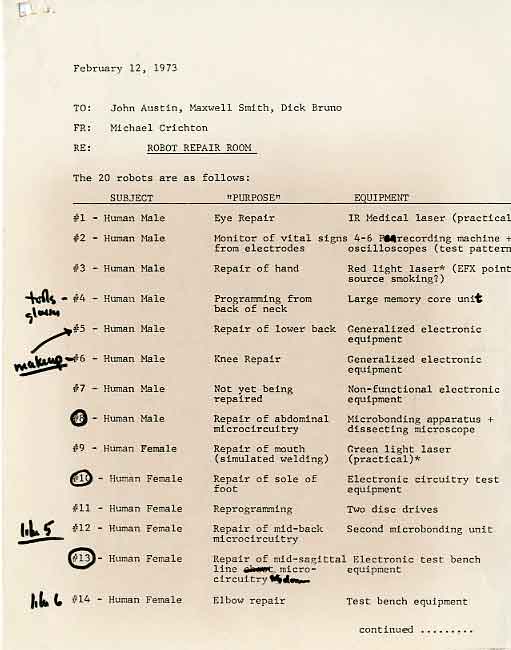

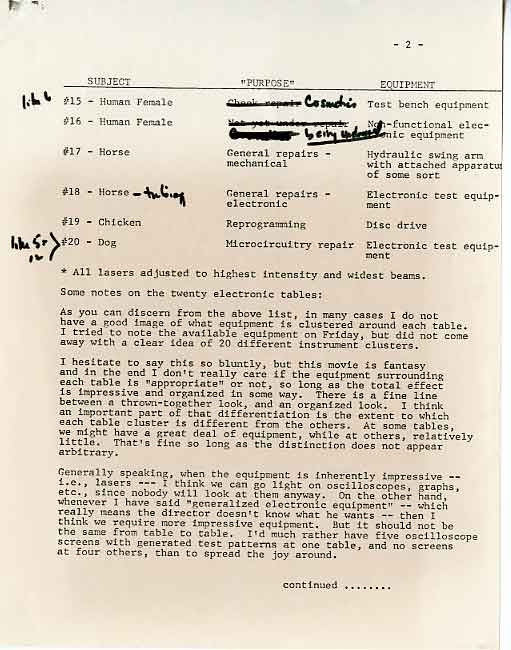

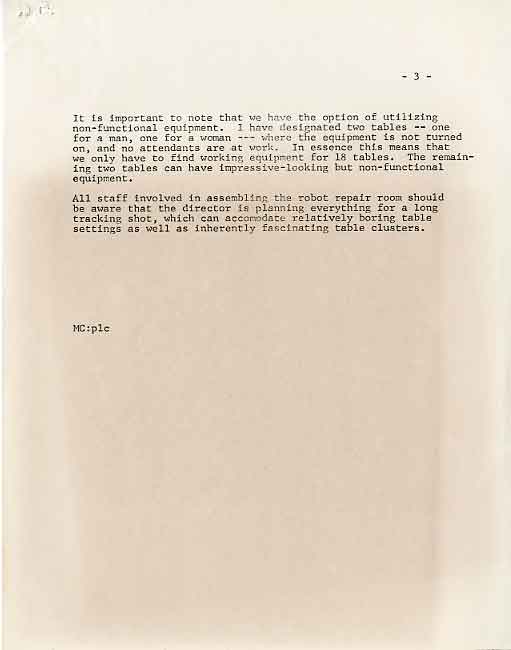

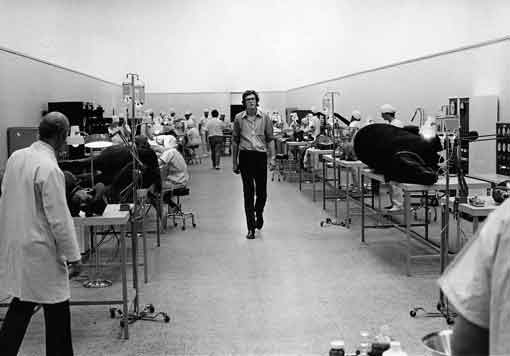

In this memo to his Production Design team, Michael Crichton explains the look he wants for the Westworld Robot Repair Room.

“I hesitate to state this so bluntly, but this movie is fantasy and in the end I don’t really care if the equipment surrounding each table is “appropriate” or not, so long as the total effect is impressive and organized in some way. There is a fine line between a thrown-together look, and an organized look.”

In His Own Words

Each specific budget category was so thinly financed as to seem impossible. Out of that $600,000 we could give the art director, Herman Blumenthal, only $75,000 for set construction. Anyone who has ever considered building a larger garage or finishing a basement playroom will understand the dimensions of his problem. For that $75,000, Herman had to build twenty sets covering nearly 200,000 square feet. And although he had certain advantages over standard construction requirements, he also had certain special problems. His floors had to be built with such fine tolerances that a camera rolling over them would not wobble or bounce. Many interiors had to be aged. The detail work had to be excellent because minor flaws become glaring when the image is projected on an eighty-foot-wide screen.

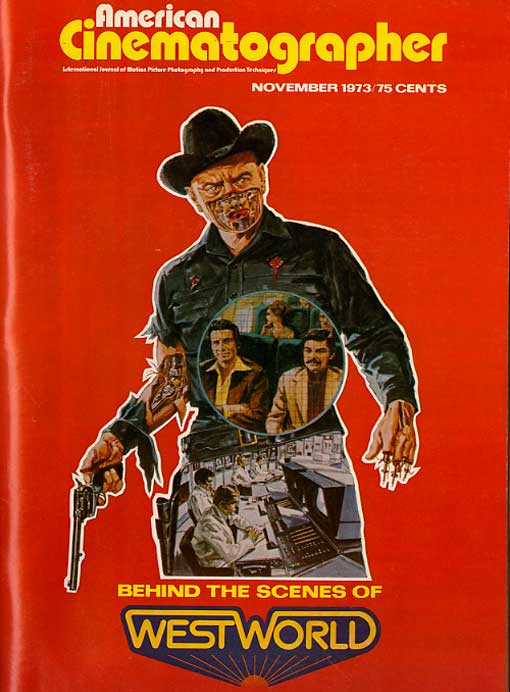

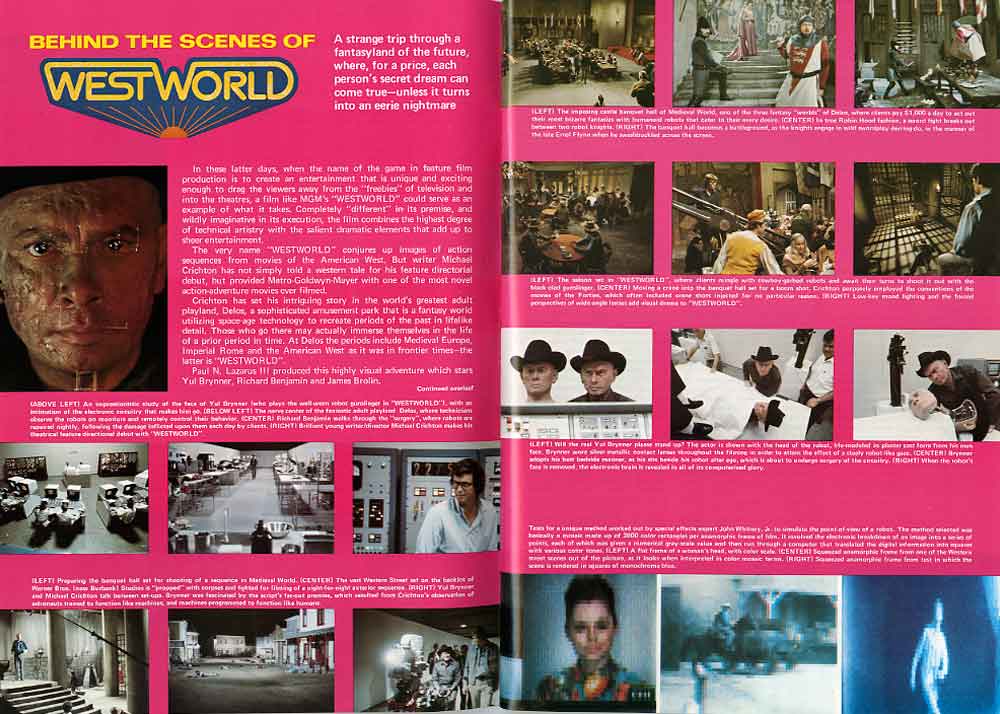

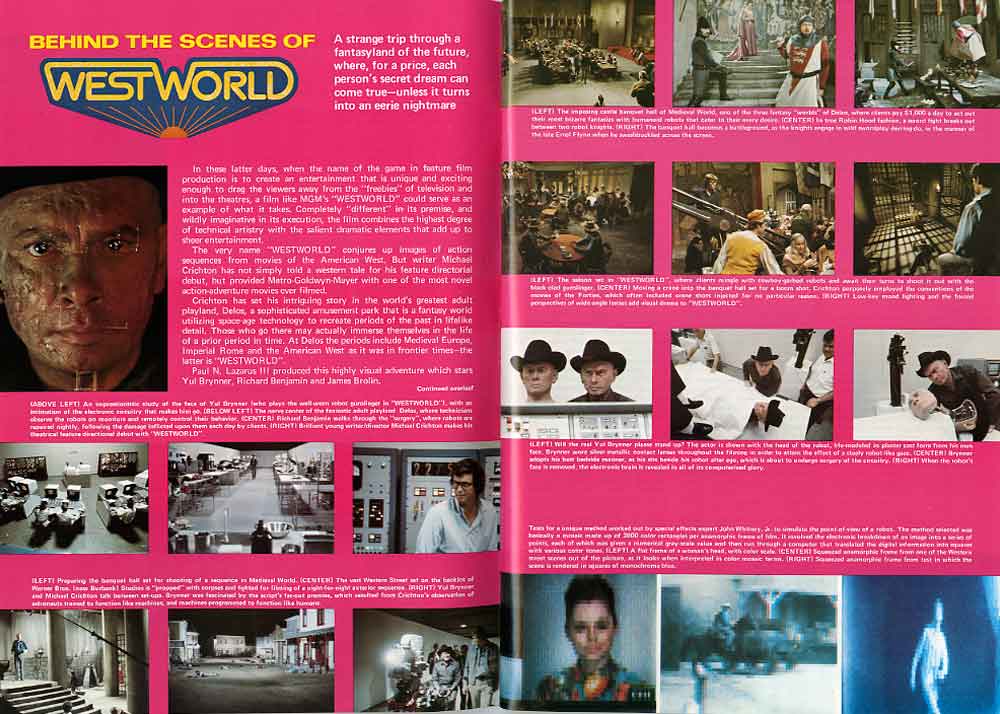

Behind the Scenes

of Westworld

American Cinematographer magazine dedicated an entire issue to Westworld in November 1973. Here’s an excerpt from Michael Crichton’s interview:

“I’d visited Kennedy Space Center and seen how astronauts were being trained – and I realized that they were really being trained to be machines. Those guys were working very hard to make their responses and even their heartbeats, as machine-like and predictable as possible. At the other extreme, one can go to Disneyland and see Abraham Lincoln standing up every 15 minutes to deliver the Gettysburg Address. That’s the case of a machine that has been made to look, talk and act like a person. I think it was the sort of notion that got the picture started. It was the idea of playing with a situation in which the usual distinctions between person and machine – between a car and the driver of the car-become blurred, and then trying to see if there was something in the situation that would lead to other ways of looking at what’s human and what’s mechanical.”

In Westworld, Michael Crichton was the first film director to use computer generated imagery as a movie special effect, marking this 1973 movie as the beginning of the development of motion picture CGI. Learn more in our Programmer and Visionary sections.

In His Own Words

I make up little stories about how I get ideas, but I really don’t know most of the time. I think I got the idea for Westworld because I was very interested in the astronauts. I was fascinated by the fact they were being trained to be machines. Then I was also fascinated by the animated figures at Disneyland. The two tendencies toward making people as machine like as possible and machines as human as possible are creating a lot of confusion. That’s what suggested Westworld to me. The tendency to make concessions to machines can only grow. Zip codes, for example, are a concession to machines. There are advantages and disadvantages to this tendency. I don’t think that people are strongly threatened by zip codes; it’s inevitable that we accommodate ourselves to the machines we need to support our existence.

Westworld (Movie)

| Release Date: | November 21, 1973 |

| Running Time: | 1 hr. 28 min. |

| MPAA: | PG |

| Director: | Michael Crichton |

| Screenwriter: | Michael Crichton |

| Studio: | MGM |

| Starring: | Yul Brynner, Richard Benjamin, James Brolin, Dick Van Patten, |

Westworld was MGM’s top grossing movie of 1973.

HBO’s Westworld Television Series

Entertainment Weekly has a great interview with the producers of HBO’s Westworld television series. You’ll want to read the whole thing but here are a couple of excerpts:

“Here’s what you already know: HBO’s upcoming Westworld is an adaptation of the 1973 film written and directed by visionary author Michael Crichton. Like the author’s best-known work, Jurassic Park, it’s about a theme park where rather unique attractions (in Westworld’s case, lifelike androids) break from their assigned roles and kill the guests.

HBO’s series version is from Interstellar and The Dark Knight co-writer Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy, along with mega-producer J.J. Abrams and Jerry Weintraub and Bryan Burk. It boasts an impressive cast led by Anthony Hopkins (in his first TV series regular role), James Marsden, Evan Rachel Wood, and Jeffrey Wright.”

“In that usual Michael Crichton fashion, he never wrote anything that was just a film-there was always a massive world behind it that could be mined.” – Jonathan Nolan

“Crichton wrote this as an original screenplay and then directed it. There’s no book. What you feel in the film is there’s this larger world that he barely has time to explore. It leaves you breathless. Westworld goes from one f-king massive idea to the next. At one point in there, he references why the robots are misbehaving. He describes the concept of the computer virus. When they were shooting the film it was the same year, or the year before, the appearance of the first actual computer virus. This is why Crichton was so brilliant. He knew so much about the technologies that were about to emerge, spent so much time thinking about how they would actually work. Consider the fact that the original film was written prior to the existence of even the first video game. Think about massive multiplayer roll-playing games, and the complexity and richness of video game storytelling. When he wrote Westworld, none of that existed! So it’s a film that anticipated so many advances in technology. The film has a structure that barrels forward—there’s this unstoppable android hellbent on vengeance-and it preceded The Terminator by 10 years.” – Jonathan Nolan

“The back of napkin version, is that it’s about a theme park where you can take your id on vacation. But there’s way more to it. It’s based on a film that’s 40 years old, and one of the amazing things about Crichton is he was such a visionary. For much of science fiction, it felt like so many of the questions were a long way away. I actually think we’re in a moment now where these questions are close in the real world. Our world is about to get very off, and some of the questions Crichton had in his film we’re hoping to elaborate on in the series. As exotic as they seemed years ago, they are now becoming very frighteningly relevant.” – Jonathan Nolan