Electronic Life

In His Own Words

This book began as practical notes for friends who had just bought home computers, and were now staring with horror at their new acquisitions. I would help them get started and leave a set of these notes for reference. Because my notes were written on a word processor, I added a little more each time. I began to get feedback. You should have mentioned this or that, they’d tell me. The notes began to get longer and longer.

I began to realize that first-time computer users needed help with something not covered in most books and manuals – namely, an attitude to take toward this new kind of machine. How to think about computers, not just how to use them.

Meanwhile, I had started to develop computer programs for film production, a business that previously used no computers at all. I was plunged into a whole new world: buying minicomputer hardware, supervising programmers, and trying to convince suspicious specialists that their lives would be simpler and better (and they would not lose their jobs) if they used these machines. The new programs were easy to use, but visitors became so anxious around a computer terminal they couldn’t recognize that they could save millions of dollars using them.

Again I was thrown back to attitudes.

In June 1982, I attended the International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado, and watched professionals in another field struggling with computers and what they meant. Once again, attitudes seemed critical.

Computers really are unprecedented machines in everyday life, and they do demand a whole set of new attitudes. This leaves people feeling helpless and lost. I hope this book helps. At the very least, having written it, I can stop talking about it myself.

Synopsis

In the early 80’s the computer began to take on a more important role in business, in education and in the home. The primary obstacle between computer manufacturer and user was language. People thought computers were too complicated and of benefit only to those specially trained in its use. Words that have now become part of our vernacular like “hard drive,” “floppy disk” and “application” appeared to be a foreign language. Michael Crichton saw the need for an easy-to- understand guide explaining the new world of computers to “regular people.”

Electronic Life was created as a layman’s guide to computers. It explained simply, concisely and without jargon what computers really are, how to choose them, how to use them, how to think about them, how to live with them, how to get them to help you, how to keep them in their place, how to enjoy the, It described step-by-step instructions on what to do when you first approach a new computer to sound advice on how to stop your computer from causing trouble in the family. His message: Don’t be afraid of them, they’re only machines, they’re here to make your life easier, and, what’s more, they can be a lot of fun.

Passage 1

The history of the telephone provides an instructive example of what happens as a technology becomes widespread. Anyone over the age of fifty can probably remember when telephones had no dials. To make a call, you picked up the receiver and waited until an operator came on the line. You told the operator the number you wanted, and the call was placed for you. If you placed a long-distance call to some other city – a very exotic undertaking – you’d hear the operators talking to each other in their regional accents, arranging to route your call through their individual switchboards.

By the 1940’s, this charming system was breaking down. There simply weren’t enough operators to work the switchboards. In fact, projections of future telephone growth suggested that there weren’t enough women in America – even if they all became telephone operators – to make the system run.

The solution was direct-dial telephones, which demanded all sorts of automatic switching devices and complex thingamajigs. This flashy new technology obscured a basic truth. The telephone company had actually solved the problem of insufficient operators by making everyone into his own operator. The number of telephone operators now equaled the telephone-using population.

For nearly everyone, the telephone provided the first experience of direct interaction with a computing machine. People had to learn the harsh rules of computer interaction: numbers only, and numbers presented in specific order. The telephone responded to exactly what you dialed, whether you’d made an error or not. There was no friendly human voice to catch your mistakes.

After an initial period of grumbling, people discovered they preferred direct dialing. It was faster and it was totally private. The few situations where an operator was still required, such as overseas calls, became irritating. The fact that you couldn’t do it yourself was now perceived as a flaw, not a virtue.

Passage 2

Most users end up wanting more Random Access Memory. The history of small computers has been characterized by increasing amounts of RAM. The earliest machines had only 4K; most machines are now sold with at least 16K, and many users feel unhappy without at least 64K. What’s it all for?

In the first place, the machines rarely allow the user all the RAM. Besides their own ROM, computers frequently eat into RAM for such tasks as running the disk drives, handling additional languages or connecting to peripheral equipment. A disk drive may consume 10K of RAM; a language interpreter another 10K. A page of graphics may require 8K, an animation 16K. At this rate, 64K of RAM disappears fast.

Furthermore, as users become accustomed to their machines, they begin to want simultaneous processing. When you start using a word processor, you find it’s a wonderful time-saver. But after you’ve typed in your text, you must wait while the machine checks spelling. Then you must wait while it prints out your pages. You forget that the whole procedure is many times faster than you could ever do it before. All this waiting around for the machine gets on your nerves. You start to wonder why the machine can’t simultaneously check spelling and print out while you keep typing.

Or if you’re working with graphics, you wonder why you can’t have more detailed images, in more colors, drawn faster. If you’re programming, you want more English like languages.

Whatever the reason, you end up wanting more memory. And machines with 512K to 1000K of RAM will be commonplace by the mid-1990’s.

Passage 3

In 1967, all students at the Harvard Medical School were required to take a biostatistics course. At this time there was a newly emergent class of specialist, called biostatistician, who was consulted by working biologists with the same frequency that Mafia hit men consult their lawyers, and for the same reason – to ask, “Can I get away with this?” Is my work unobjectionable?”

Thus in 1967, to teach biostatistics to every medical student had its revolutionary aspect; the idea was to make all young doctors self-sufficient enough to carry out their own statistical analyses, and to evaluate those of others. It was imagined we would read every journal article critically, and then sit down with pencil and paper to scratch out the calculations and determine if the authors had done their sums correctly or not.

But this focus on self-reliance (and a rather prissy instructor) led to a final examination where we were expected to calculate standard deviations by hand. And the calculation of standard deviations requires the calculation of square roots by hand.

I’d done a lot of statistical work before medical school, and although I set up the formulas on paper for my final, I flatly refused to do these calculations by hand. Desk-top calculators were available for such drudgery; every lab had them. I pointed this out.

And I went further. I predicted that within ten years there would be calculators the size of a pack of cigarettes, and costing only a hundred dollars. Thus, I argued, there was no need to bother doing square roots by hand, since it as a virtually obsolete skill.

For this bit of prediction, I got a sarcastic note in red pencil, and a D grade. My instructor took pains to remind me that desk-top calculators in 1967 were larger than a typewriter, weighed more that thirty pounds and cost several hundred dollars. My instructor disagreed that they would ever become as small and cheap as I claimed in my lifetime, let alone in ten years. He made some further nasty remarks about my propensity for science fiction, and underlined the D grade twice, emphatically.

Texas Instruments sold the first pocket calculators in 1971.

From the Archives

In a 1983 article promoting Electronic Life, written by Christine Sinrud Shade for Micro Discovery magazine, Michael Crichton is asked about the necessity of a home computer:

Does the average person need a computer? “You probably don’t” says Crichton. “Just like you don’t need a TV or a microwave oven.”

In His Own Words

I wrote Electronic Life as much to suggest problems with them [computers] as to encourage people to use them, My feeling really was that these little machines are now here. Instead of having some kind of fictional book or movie in which the access to computers is a very distant notion, something in the hands of specialized people who presumably know what they’re doing, that everyone’s going to be able to use them and interact with them and they’re going to be very inexpensive and ubiquitous. And that calls for a balanced attitude.

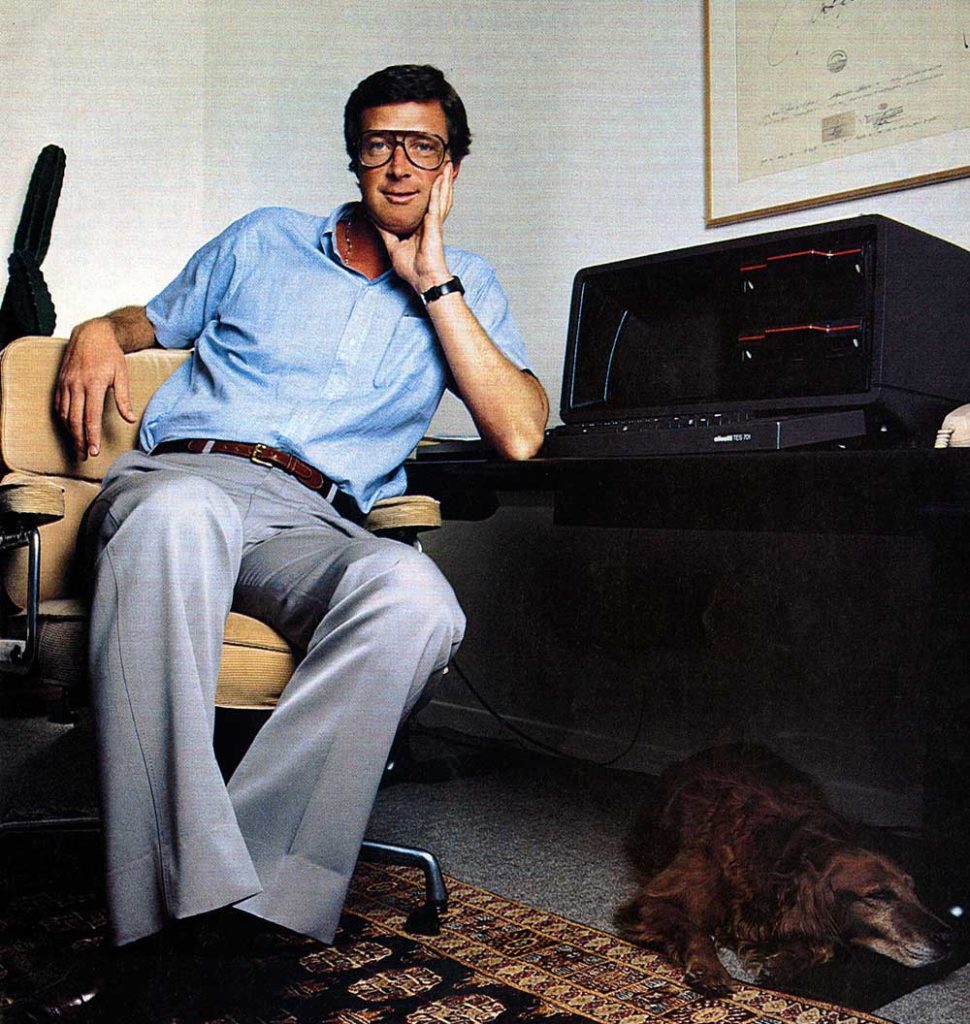

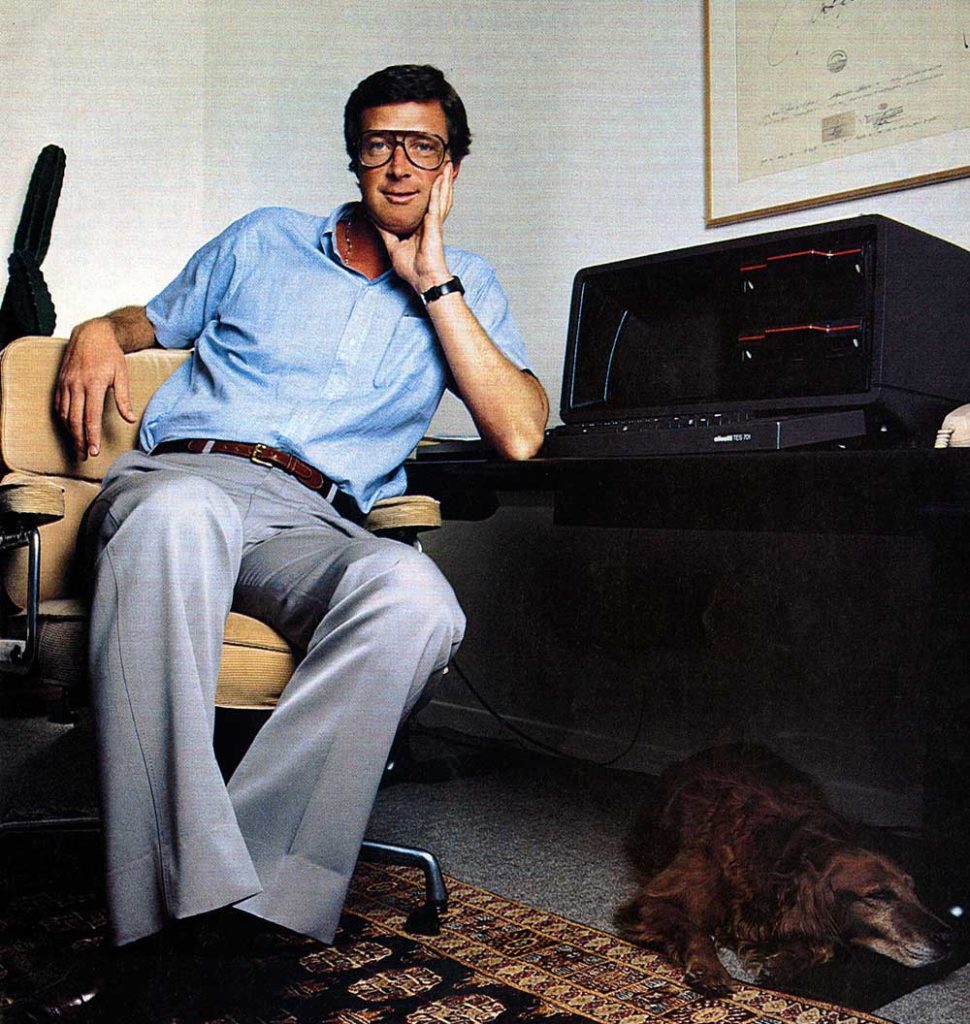

In 1984, Michael Crichton was interviewed by Alan Cheuse for an article called “Standing Out in the Crowd: The Diversified Genius of Michael Crichton: Modern Man of Medicine, Films, Books and Computers” that was published in the HCA Companion. In it he talks about Electronic Life, computers and technology including his first word processor:

“My senior thesis was a study of ancient Egyptian racial history,” he explains, “and I had the data analyzed by the computer. In those days you were not allowed to touch the machine yourself, but I had made up the punch cards for programming. Then, at Harvard Medical School, and at the Salk Institute, I used computers all the time in my research. But when I became a full-time writer I really didn’t have access to computers for a long time. In 1977, I got an Olivetti word-processor, and have been writing my books on it ever since. I find that it takes away all the mechanical problems of writing and allows you to concentrate on the quality of the prose.”

Book Covers