Spotlight on Michael Crichton's Visionary Influence

Not unlike Jules Verne, Michael Crichton predicted, speculated, and projected what may be in our future. Even today, his work challenges us to better understand who we are, where we came from and where we are going. Michael Crichton intuitively observed the importance of being sympathetic to the environment, to projecting this sentiment into the future, and recognizing and addressing our past failures. His empathy for the betterment of human life combined with his vast knowledge of medicine, technology, anthropology, and science, made Michael Crichton a man ahead of his time and a true visionary.

In His Own Words

[On how it feels when his books turn out to anticipate real-life events or trends.] It depends. People said Airframe was prescient when a United Airlines flight dropped 1000 feet over the Pacific. But there are a certain number of turbulence-related injuries every year, and that book was based on a couple of real incidents. The lesson “Wear your seat belt.” When Twister came out in May of whatever year it was, all these tornadoes hit. Everyone said, “Isn’t it amazing? He predicted it!” No, it’s May — there are always hundreds of tornadoes. It’s tornado season. On the other hand, certain things have surprised me. When I was working on The Great Train Robbery, I went into Victorian England, then an eccentric and obscure period to write about. At the time the book was published, the period had a revival. When I was writing Rising Sun, the Berlin Wall was coming down. Everyone was looking west; no one was looking east. People would ask what I was working on and I’d say “Japan” and they’d ask, “Japan?” as if I had said “Sanskrit.” But when the book came out it coincided with George Bush’s trip to Japan and enormous interest in U.S.-Japanese relations because of the trade imbalance. I was as surprised as anybody else.

1969 – The Andromeda Strain

The Andromeda Strain stands as the first popular work to alert the public to the growing power of biological science, and to hint that biology would eventually replace physics and nuclear technology as a source of public concern and interest. Thus, the hazmat-suited figures that were so exotic in the movie over forty years ago are now all-too-common.

1973 – Westworld

The Boss Villain

Westworld’s Gunslinger Robot is the predecessor of Darth Vader in Star Wars. It is the predecessor of The Terminator. It is the predecessor of all the Boss villains, the unbeatable super opponents, that came after 1973.

Yul Brynner as The Gunslinger in Westworld, 1973. Photo credit: MGM

Darth Vader, Star Wars, 1977. Photo credit: 20th Century Fox.

Arnold Schwarzenegger as The Terminator, 1984. Photo credit: Orion Pictures.

Groundbreaking Special Effects

In Westworld, Michael Crichton was the first film director to use computer generated graphics as a movie special effect. Michael Crichton worked closely with graphic artist John Whitney JR. and his Visual Effects team to create special computer generated “pixelated” sequences that would show how the Gunslinger robot viewed the world. These sequences, which you can see in this clip from Westworld are the very first attempts at motion picture CGI.

In His Own Words

I had plenty to worry about until then. The computer-generated footage was coming in, far behind schedule. John Whitney had found the process unexpectedly time consuming—it took eight hours to produce ten seconds of film. There were intricate problems with color and contrast balance. We were still doing a lot of testing. On the other hand, we were pleased with the general effect.

1980 – Congo

In His Own Words

I do some reading, then I sit down and try to imagine–from the research, from my general knowledge and understanding of these things–what things could really be like. You have to immerse yourself in current events and then let your mind go free, see what you can imagine to be the next development. If I can imagine it, someone else is already doing it.

Take Congo for instance– I knew that many people who were doing research with primates, teaching them sign language, were interested in taking these animals back to Africa. So I was in a panic that someone would actually do it before I could get the book out. In fact, all of my best ideas that I made up were turning out to be true at such a furious rate that I was quite nervous.. For example, the idea of super-conducting computers, which appears in Congo. I very carefully explained why superconducting computers were the next generation of computers. That became the cover story of Scientific American about eight months before my book was published. When I saw the article I thought, my God, this looks like plagiarism— the argument in the article was exactly my argument. But by that time my book was in galleys! Similarly, I thought, well, a computer that used light instead of electricity would be a wonderful idea. And that was the cover story in the New Scientist before the book was published. So I had this terrible feeling of trying to get the book out before all this was ancient history.

There are many areas in Congo where Michael Crichton imagined a future innovation that was soon to become reality—remote sensing and microelectronics to name two. But it was the field of primate studies that took center stage in the story of a gorilla named Amy who had been taught sign language. Many reviewers did not believe that gorillas could sign. It would not be until five years after the publication of Congo that Koko the Gorilla would become famous in the children’s book Koko’s Kitten.

Congo (1980) and Koko’s Kitten (1985)

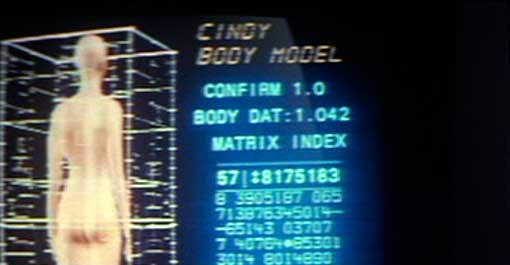

1981 – Looker

Looker, the sci-fi movie Michael Crichton directed in 1981 also used never-seen-before visual effects. As explained on Filmsite.org’s Film Milestones in Visual and Special Effects:

“The visual effects in Michael Crichton’s high-tech science-fiction thriller featured the first CGI human character, model Cindy (Susan Dey of The Partridge Family fame). Her digitization was visualized by a computer-generated simulation of her body being scanned – notably the first use of shaded 3D CGI in a feature film. Polygonal models obtained by digitizing a human body were used to render the effects.”

In His Own Words

At the time we made this movie, there was digitization which is now done all over the place. It’s done for computer games, it’s done everywhere. There was a single digital scanner, in I think, Dallas. And I think it was a NASA scanner, I’m not sure. And so if you wanted to do a total body scan, like this, you had to send your person to this place. I think they did it with physical points. Like those, I don’t know if you’ve ever seen those pin things where you push your hand in and it shows the image of the pin, well I think it was like that. That there were literally physical points that would touch the person. Now it’s all done with lasers and it can be very distant. Susan [Dey] was not enthusiastic about doing the scene undressed and unfortunately this took actually days and days and days, poor girl.

1983 – Electronic Life

When Michael Crichton wrote Electronic Life in 1983, there were 233 million people living in the United States of America. That same year, only 3 million small computers were sold – half of those going to businesses. At that time, having a computer in your home was a luxury that very few people enjoyed. But Michael Crichton saw that the future was changing and that a time was coming when everyone would have a home computer.

In His Own Words

Oh, the electronic world is very different from the way it was when I wrote Electronic Life eighteen years ago. There are a lot of changes. However, I’m pretty impressed by what I got right. For example, the book anticipates the rise of the Internet, and the idea that you would use your computer for communications, for linking to specialized user groups, etc. Which is not bad as a prediction nearly two decades ago. (The DARPA net existed back then, of course, but only as a government/academic network.) As for what I missed, I guess the biggest thing was faxes. I did not anticipate that document transmission would be done by stand-alone machines. In fact, they now seem to be a transitional phase. More and more document transmission is now straight computer-to-computer.

1984 – Runaway

When Michael Crichton wrote the screenplay for Runaway in the early 1980’s there was no graphical user interface for computers. The Macintosh desktop would not debut until after the movie was released in 1984 and Microsoft Windows would not be available until late 1985. Cellphones still looked (and felt) like bricks and music on CD had just debuted. Which makes the technological gadgets that Michael Crichton conjured up for his futuristic police movie over 30 years ago so impressive. Here are ten things that appeared in Michael Crichton’s movie that are only now becoming available:

Camera Drone in Runaway

Headline from 2014:

Paparazzi Now Using Drones to Hunt Down and Photograph Stars

Domestic Robot in Runaway

Headline from 2015:

The Robots Moving in to Your House

Tablet Computer in Runaway

Headline from 2010:

Apple iPad: Everything You Need to Know

Suspect Sketch Computer Program in Runaway

Headline from 2014:

Programs Allow Victims to Create Digital Sketches of Suspects in Crimes

Robot Security Guard in Runaway

Headline from 2014:

Microsoft Turns to Robotic Security Guards to Watch for Trouble

Smart Bullet in Runaway

Headline from 2014:

Microsoft Turns to Robotic Security Guards to Watch for Trouble

1990 – Jurassic Park

At the heart of Michael Crichton’s most famous novel, Jurassic Park, is the myriad of technological and ethical questions regarding the idea of bringing extinct species back to life. In a September 1993 issue of Southwest Airlines’ Spirit magazine by Mark Seal, Michael Crichton relates a story about whether or not dinosaurs could really be cloned:

“Crichton likes to tell the story of running into a group of biotechnologist friends in Hawaii after Jurassic Park was published by Knopf in early 1990. Eager for feedback, he showed them the book.

“I had some concern that they might dislike it because it was critical of biotechnology,” he says. “My idea in that book was to suggest that we shouldn’t make dinosaurs. And theirs was, ‘Why not?’ And the first person, a very famous biotechnologist, read it and put the book down and said, ‘It can be done!’ and got excited. There’s actually been a fair amount of research that’s been promoted or stimulated by the book.”

Can it be done?

“Not now,” Crichton says. “I think (the biotechnologist) was saying that the story has no theoretical barriers, you know. It doesn’t require you to travel faster than light. … I would be very surprised if we didn’t have the revival of some extinct animals, possibly within a decade.”

He was a little too ambitious on his timeline, but it seems that the ability to clone long dead species is indeed upon us. In this PBS article called, “Should Scientists Bring Extinct Species Back from Oblivion?”, they say:

“Ever since the 1993 blockbuster Jurassic Park, the possibility of bringing extinct species back to life has been part of our collective imagination. The film, based on a Michael Crichton novel, was itself inspired by actual scientific breakthroughs in the early 1990s that allowed scientists to use DNA from museum specimens and fossils to recreate the genome — or genetic blueprint — of dead animals. When the film debuted, the science wasn’t advanced enough to bring back extinct species. But today it might well be, and researchers’ growing efforts to recreate extinct species — in labs from California to Australia — have been making headlines.”

1993 –

Mediasaurus Speech

On April 10, 1993, Michael Crichton gave a speech to The National Press Club called “Mediasaurus: The Decline of Conventional Media.” This speech made quite a splash at the time for predicting the decline of mainstream media. Michael Crichton predicted it would happen faster than it did, but the thrust of the speech is clearly correct.

In 2008, Jack Shafer from Slate Magazine wrote an article looking back at the speech called: Michael Crichton, Vindicated: His 1993 prediction of mass-media extinction now looks on target. Here’s an excerpt:

“As we pass his prediction’s 15-year anniversary, I’ve got to declare advantage Crichton. Rot afflicts the newspaper industry, which is shedding staff, circulation, and revenues. It’s gotten so bad in newspaperville that some people want Google to buy the Times and run it as a charity! Evening news viewership continues to evaporate, and while the mass media aren’t going extinct tomorrow, Crichton’s original observations about the media future now rings more true than false. Ask any journalist.”

2004 – State of Fear

In Michael Crichton’s State of Fear, he challenged politicized science and computer models. There has been much controversy and misinformation about Michael Crichton’s views on these subjects. Michael Crichton lays his viewpoints out at the end of his book and you can read them here.

2006 – Next

Michael Crichton was not one to be political but was always willing to take a stand to amend an injustice. After publishing Next in 2006, Michael Crichton advised policymakers to ban gene patents and establish clear guidelines for patients rights. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that genes cannot be patented in 2013.